Extracted from Bubba:

How the Predator-in-Chief pulled it off.

Buy Bubba. Then: Bye, Bubba!

A Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie story

September 16, 2001

“Mr. President, before we begin I need to remind you that reality television is still television.” Manny Kant said that. His hands were folded together, his thumbs pressed tightly to his lips. His hair was slicked back and his tiny black eyes were hidden behind tiny mirrored sunglasses.

Dubya wore a look of profound confusion, which is basically the ground state of his face.

“What I mean is, the pilot got great ratings, phenomenal ratings—”

“But not one cent in advertising,” Fishman interjected. He was sitting to Manny’s right at the conference table, growling around an unlit cigar.

“But not one cent in advertising,” Manny agreed.

“I believe you gentlemen have lost me,” said Dubya. “What’s this pilot we’re talking about?”

“This week, Mr. President,” Manny replied. “Television. Wall-to-wall, sign-on to sign-on, twenty-four-hour continuous coverage.”

“Who would have thought that so little could be regurgitated so many times? To such huge audiences…” Wakefield said this, a sly kind of post-modern wonder in his voice.

We were sitting in a hotel conference room in Arlington, Virginia, the five of us: Manny Kant and his two minions, Dubya, and me. Don’t ask me why I was there. My guess is that Manny was showing off. I’ve known him since he was a greasy little peddler on the streets of New York, selling empty soda cans with a soft con. Later he had me along when he launched the Corpse brand of cigarettes, a daring experiment in honesty in advertising. Now he’s director of programming for a major television network, and I think he was just taking another chance to gloat at my astonishment.

And don’t ask me how a craven hustler like Manny Kant gets to program a TV network. Nature abhors a vacuum, would be my guess. Which is the nice way of saying that scum rises to the top. In a culture of unreason, every outcome is necessarily the consequence of thoughtlessness…

“Anyway,” said Manny, “we can’t afford to take chances. It might be reality TV, but we’ve still got to give it the juice.”

“The juice…?”

“You know,” said Wakefield. “Conflict. Drama. Schism. Spasm. Rhythm. Action. The juice.”

“And a love interest, don’t forget that,” said Fishman.

“And suspense,” Wakefield continued. “And surprise. And irony. And some kind of comic side-kick.”

“And sex,” Fishman added. “Lots of sex.”

“And explosions, of course,” said Manny, “But it’s a war, after all. There’ll be plenty of good explosions, right?”

“Explosions…?”

“Yes, Mr. President, explosions. You know, like Bruce Willis, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Mel Gibson. We’ll need one explosion per segment.”

“Per segment…?”

“Yes, Mr. President. A segment is the interval between commercials. It lasts nine minutes. We crunched the numbers on this, and there’s no possible way we can produce a TV war without at least one significant explosion per segment. We’ll need at least one major explosion per half hour. We can replay the better ones – you know, slow motion, stirring music, dissolve to the flag, that kind of thing. Just like we did with the collapse of the Twin Towers. But we still need the basic content, one explosion per segment, one major explosion per half hour.”

Dubya said nothing to this. He simply looked confused. And scared. And lost.

“Don’t forget the counterpoint,” said Wakefield.

“That’s right,” Manny agreed. “And if I may say so, Mr. President, you’ve done great work here. The airport restrictions are simply stunning. Teeny-tiny plastic picnic knives! As weapons! You can barely penetrate mayonnaise with those things! That’s priceless!”

“Yeah, that’s good,” said Wakefield. “How about a bunch of grandmothers who hijack a plane with their hatpins?”

“Or how about gang-bangers who strangle the flight crew with their belts,” Fishman suggested. “You can’t take away their belts. Those baggy pants would fall right down.”

“Yeah,” Wakefield agreed, “or how about a riot in first class when they serve London Broil with no steak knives?”

“This is good stuff,” Manny said. “It’s the counter-example. It’s the contrast. It’s the irony. Got any plans to crack down on the internet? Or encryption? Or firearms? I mean, if you can take away our picnic knives, why not our handguns, too?”

“I don’t understand you,” Dubya insisted. “America is about freedom…”

“Like fun!” Manny chortled.

“Not since Franklin Roosevelt!” Fishman sputtered.

“Not since Teddy Roosevelt!” Wakefield gasped.

“Not since Arbraham Lincoln,” Manny concluded sagely. “He freed the slaves and enslaved everybody else. Now that’s dramatic irony. What great television that would have made…”

“Great— television…?”

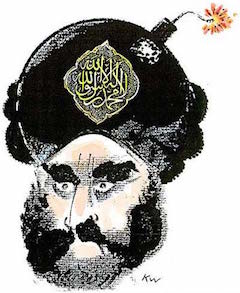

“Oh, don’t take me the wrong way, Mr. President,” Manny protested. “This is great television, too. It’s the great swarthy villain, the great, nondescript, largely-undifferentiated, thoroughly politically-correct bogeyman. Who’s the enemy? It’s the other. Dark skin. Dark hair. Bad English.”

“Bad beards,” said Fishman.

“Bad hygiene,” Wakefield agreed, primly.

“It’s the Not-Us,” Manny continued. “Not anything we know or understand. Or want to know or understand. It’s everything we can safely hate, without feeling guilty. It’s everything we think we’re not.”

“And that’s the irony!” Wakefield practically shouted.

“Irony?” said Dubya. “I’m not that good at irony.”

“Clearly,” Manny drawled. “But this can’t be that hard to see. ‘America is about freedom’ – except if you want a picnic knife to spread the mayo on your lousy airline sandwich. You get us all worked up about terrorism while you tighten the noose around our necks, inch by inch, hour by hour, episode by episode. This is gripping television, Mr. President…”

“I’ve thought about this,” Wakefield exclaimed. “You have to grow a beard, Mr. President. Just a five-o’clock-shadow at first, like you’re too busy with the war to shave. But as we go along, the beard gets longer and longer. Then you go to visit the troops and get a deep, deep suntan. Then we do a shot where we dissolve from a close-up of the villain to you, the one becomes the other. That’s the cliff-hanger at the end of the season…”

“End of the season? This war could take years…”

“Thirteen weeks,” Fishman growled. “Thirteen weeks with an option to renew, just like everybody else.”

Dubya looked glum. And scared. And sad. And tired. And confused, always confused.

Manny pulled his hands away from his face and smiled. “Mr. President, we couldn’t do any of this without you. Al Gore campaigned for two years for airport slavery and he got nowhere. And he never even thought of confiscating the picnic knives! You’ve given us more tyranny in a week than Clinton and Gore gave us in eight years, and this war of yours is barely started. The one becomes the other, inch by inch, hour by hour, episode by episode. Thirteen weeks? Mr. President, I predict this show will still be getting great ratings in thirteen years!”

Dubya sat up a little straighter. He said, “It’s a war, gentlemen, not a show.”

“Yeah,” said Manny Kant. “Right…”