“But education doesn’t stop when we’re toddlers; that’s when it begins! And that’s when we hand the reins over to the ‘educators’, the ‘professionals’. And they take children enslaved by their ignorance and lead them to the charnel house of tedium, teaching them nothing and leaving them no outlets for their energy but self-destruction. Is this what you went to all that trouble for, so your children could grow up to be book banners, book burners, self-righteous champions of eternal savagery?”

October 23, 1996

“Mark Twain said, ‘In the first place God made idiots. This was for practice. Then he made school boards.’” There was a smattering of uncomfortable laughter throughout the school gymnasium, accompanied by pained looks from the dais, where the school board sat. “I’m not here to talk to practiced idiots. I am here, though, to stand up for Huck Finn.”

And yes, Uncle Willie was giving a speech. Wearing a jacket and tie, no less – finest quality thrift shop haberdashery. I was shuffling through Jefferson, Oregon, shuffling my way to somewhere less moist, when that gray and soggy city was struck by the national craze to ban Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn” for using the N-word.

The N-word, in case you were wondering, is “nigger”. Not “north”. Not “nitrogen”. Not even “nebulous nincompoop non-communication”. It’s “nigger”. I think it says something rather profound about the life of the mind in latter-day America that we have become used to conversing in meaningless euphemisms. “Intestinally deficient,” to say the least of it.

Anyway, you know the story; it shows up in the papers five or six times a year. Some snotty little proto-teen decided that blowing off her homework was a human rights issue, and some sleazy little ‘educator’ made a media circus out of it. It is a testament to the progress of the Politically Correct “idea” that it is now possible to be a jackass by proxy. I showed up just as the school board members, hand-crafted idiots made with pride by a skilled and practiced god, were gearing themselves up for the predictable denouement.

“And why wouldn’t I stand up for Huck?” I asked. “In some ways I am Huckleberry Finn. In some ways we all are. And, like Twain, ‘I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.’” More laughter, maybe a little better humored.

I had a copy of “Huckleberry Finn” in my hand and I was gesturing with it like a TV preacher with his bible. I said, “You can ban this book if you want to. You’ve got the power and I can’t stop you from using it. But I’d hate for you to ban it in ignorance. I’d hate for you to ban it without knowing what it is, what it really is.” I fixed the little proto-teen with a stare, pinned her with the arrows in my eyes. “I’d hate for you to ban it without knowing what it says.”

The little teenlet squirmed uncomfortably, but her troubles had just begun. Speaking directly to her, I said, “What is it that you found so offensive about this book? Does the ink smell bad to you?” A little laughter, a little more squirming. “I don’t like the color of this cover. It’s too bright to be vermilion, too dark to be russet. It looks like blood. Are you offended by books that look like blood?” There was a little more laughter, scattered and nervous, and the little girl was furious.

“You know what’s wrong with it!” she spat. “It uses the N-word!”

I shook my head. “No, it doesn’t. It uses the word ‘nigger’. Many times. Hundreds of times. Twain had a reason for using that word. Can you tell me what his reason was?”

She said nothing, just glared.

“Well, then, can you tell me which use of the word ‘nigger’ you found offensive? Jim is black. Is it offensive when he uses the word ‘nigger’? Huck is ignorant. Surely we can’t hold him at fault for not knowing any better than to use bad language.”

“It’s the author!”

“Indeed. Do you think Mark Twain wanted to insult black people by using the word ‘nigger’? Is that the purpose of ‘Huckleberry Finn’, to insult black people?”

She started to say something then stopped herself.

“Is that what Twain was doing with the Duke and the Dauphin? Is that what he was doing with the Shepherdsons and the Grangerfords, making fun of black people? Is the incident involving Colonel Sherburn intended to malign black people?”

Her face was a mask of confusion, as I knew it would be. “Do you mean to say that you are ‘offended’ by a book you haven’t even read?”

“I– , I– , I read enough of it!”

“You want to ban a book you haven’t read. You read just enough to make up an excuse to quit, didn’t you? And in preference to admitting that, you’ll make it impossible for every child in this school district to read one of the most important books ever written. Your parents must be awfully proud…”

I swept the room with my eyes. “Because this book is not intended to malign black people. The purpose of ‘Huckleberry Finn’ is to malign and insult and ridicule white people, to grab them by the scruff of the neck and rub their noses in the mud of their own hypocrisy. Could it be that the mud runs as thick in Jefferson as it did in Colonel Sherburn’s Arkansas?

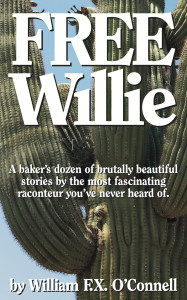

This is one of the stories collected in the free book FREE Willie.

I turned my gaze to the school board. “What do you stand for…?”

I spun back to the audience and walked my eyes from face to face. “This is what teachers do. I have no idea what ‘educators’ do. Gobble up tax dollars and quack like ducks, I guess.” Pleasant laughter. “Screech like chickens when you call ’em on it.” More laughter. “But this is what teachers do. They grab you by the scruff of the neck and say, ‘Un-ac-ceptable. Your appetites are not proof. Your passions are not proof. Your craven prejudices are the perfect opposite of proof. Your precious feelings demonstrate nothing, justify nothing, prove nothing.’”

I looked back to the proto-teen. “If you had been lucky enough to have a teacher, instead of this collection of god-mangled idiots, you would have read ‘Huckleberry Finn’ by now. You could have moved on to ‘Lord of the Flies’, which is about school boards.” That joke was pushing things, I know; irony is the hardest of mettles. “If you were lucky enough to have a teacher, you could get yourself an education.”

I swept my eyes across the room again. “We were all of us born ignorant, just like Huck. Born naked and squalling, covered in blood and mucous and bilious excrement. We are born as animals, savage and helpless and terrified and outraged and completely incompetent to do anything about it. And thus would we remain, until we died, minutes or hours later. Except that each of us was lucky enough to have a teacher – a lot of teachers – when we were young. They taught us to feed ourselves and to walk and to speak and to use the bathroom – a thousand and one things that toddlers do routinely and animals do only in performance.

“But education doesn’t stop when we’re toddlers; that’s when it begins! And that’s when we hand the reins over to the ‘educators’, the ‘professionals’. And they take children enslaved by their ignorance and lead them to the charnel house of tedium, teaching them nothing and leaving them no outlets for their energy but self-destruction. Is this what you went to all that trouble for, so your children could grow up to be book banners, book burners, self-righteous champions of eternal savagery?

“The job of a teacher is to lead children – and adults – out of the slavery of ignorance. If you had been lucky enough to have a teacher, you’d know that. The job of a teacher is to induce you to rise above your appetites and your passions and your prejudices and your fears and your feelings and to impel you to use your mind. For an instant. For an hour. For a day. For a year. For a lifetime. The job of a teacher is to teach you to conquer your fears and your prejudices and your aversions, to say to them proudly, ‘You will not enslave me, for my mind can master anything!’

“The job of a teacher is to command you to rise above the mud and excrement that is your inheritance from nature and grasp instead the legacy left you by all those great minds who lived before you.”

I pointed my finger right at the little proto-teen and said, “You are made of the same stuff as Socrates. The same stuff as Michelangelo, Copernicus, Beethoven, Shakespeare. You walk the same green Earth that Twain himself walked. You read his books – or refuse to – by the light of the same sun. There is nothing you cannot reach – if you find the right teacher.

“And the job of that teacher is to lead you out of the slavery of darkness and into the freedom of the clean, clear light of knowledge, of wisdom, of reason. To be the Moses of your mind’s liberation and help you build Jerusalem right here, in Jefferson’s gray and soggy land.”

I held my copy of “Huckleberry Finn” aloft – like a bible, like a sword, like a torch. “I don’t know how many teachers you have among all these ‘educators’. But I know this: This book is one of the finest teachers you will ever have. If you ban it, you will condemn yourselves to wallow in the mud. And you will belong there.”

The echo of my voice died to silence and the silence hung heavy in the air. I had begun to wonder if I was going to get a free ride out of town on a rail. But then a big, beefy man at the back of the gym stood up and clapped his hands together hard. He applauded with a slow cadence and, one by one, all around the room, people stood up and joined him. Surprised me, really. I figure there’s always one or two folks who are willing to listen to what I have to say, but not very many. It wasn’t everyone, even so; a stout minority of ‘educators’ and school board members sat scowling, their arms crossed, their lips pursed in tight little lines. But the parents and the real teachers rose, one at a time, applauding not Twain nor my frail defense of him, but their own love for justice and their will to grasp it.

And then, surprise of all surprises, the little proto-teen stood up and started to clap. I’d like to hope she was a little wiser for spending an hour with the muses. More probably she was mooing with the herd, not knowing that for once this group of people was not a herd. At the very least, she was chastened and chagrined. And after all, victory is where you find it. I tossed my copy of “Huckleberry Finn” to her, lofting it over the crowd. She caught it with one hand and held it high – like a bible, like a sword, like a torch.

Huckleberry Finn jumped in the river to free a runaway slave. And he’s freeing slaves still, in Jefferson and everywhere people seek deliverance from the bondage of ignorance. Huck became a human being when he resolved to stand for justice no matter what the cost. We become more perfectly human when we do the same.