“My name is Loco Willie and I am loco for frisky dogs, precocious children, classy broads and cheap, red guitars.”

Friday, December 1, 2017

“Don’t you know any other songs?” The kid we’re going to call Stingray asked me that. Tank top and cargo shorts in December, but, hey, it’s Phoenix. And he’s Stingray because we all know how he gets his scrawny ass to Walmart after school.

“You kiddin’?” said another kid, shorter and way too heavy for his age. He was in shorts, too, but Charter School uniform khakis. How do I know it’s a Charter and not a Catholic School? His corresponding polo shirt was a bright, warm red, not navy blue or forest green – and it was new this school year, not hand-me-down worn. “I’ve been standing here for ten minutes and he hasn’t played the same thing twice.”

I looked up from the guitar I was playing and spoke to Josh, who had come along for the ride. “Who’s right?”

He’s a good-looking boy, just eighteen and nine whole beard hairs to prove it. Black Irish – tall, fit and dark – and he is most definitely not my young friend Tegan’s boyfriend – which argues to me that he could use my good influence: She’s going to be a fine woman, but she’s a tough pasture to plow. He said, “Beats me. It does sound sort of the same from time to time, and yet every song is different.”

I looked to Stingray. “Tell him.”

He shrugged. “It’s just one-four-five with sevenths.” Thunk. Try again. “The twelve-bar blues?” Thunk.

I had been playing this whole time and before – mainly charging, choppy stuff – but I picked out a bluesy little turnaround as a tiny piece of musical history.

“No,” said Charter School, “every song has been different.”

“It’s just rock ’n’ roll, dude. Same song, a million different ways to play it.”

I smiled. I spoke to Josh, including the boys but ranking Josh above them. “It’s not even a song, just a chord progression. It’s ninety percent or more of all pop music, and it’s just what he said – three chords ornamented with sevenths and minors.” I still had on my Loco Willie hat from driving the choo-choo train at the mall, and I tipped it to Stingray. “Well done, son. You just schooled a Brophy boy.”

He grinned at that idea. In the Valley of the Ever-Fecund Sun, Brophy College Prep matters and everyone knows it.

“You take lessons?”

He pulled his bare shoulders in a little. “My dad teaches me. When he can.”

I didn’t wince, but I wanted to. Neither one of those boys has a father at home, not a reliable one – but that was true for all the other little men gathered around me, too. There were a few moms and sisters, standing further back, waiting with their shopping carts, but no dads.

I was making music, in Walmart of all places, and nothing draws a crowd like a crowd. But the crowd I had drawn was almost entirely tweenage boys, and every one of those boys is looking for his father. In Walmart of all places.

No moms in sight for Stingray or Charter School, but I can see their mothers from past experience. Stingray’s mom has her own burdens to bear, so he’s picking up the slack in whatever ways seem to make the best sense to his dumbass friends – all also neglected. And Charter School’s mom is vigilant but anxious, so he will wear her fears as a fat-suit of emotional armor for the rest of his life.

And there’s only so much you can do in a day, so I did what I could: I played louder.

Josh had picked me up at the Choo-Choo Train kiosk at The Arrowhead Mall after he got out of school. Driving in Phoenix at Christmas is so awful that only teenagers like to do it, so I let him drive us up the road a mile to Walmart. Barely took twenty minutes.

What were we up to? Tegan has been bragging to him about some of the Willie games she’s run with me over the years, and Josh wanted to take a turn. Plus which, I cannot get enough of Walmart at Christmas.

You sneer, but that’s because you’ve never had to choose between used-and-broken and new-but-cheap. Walmart gives poor and thrifty people choices – and I mean a lot of them. The merchandise is not stacked quite as high this Christmas – but it’s still an acre or two of incredible values: Almost-as-good for a-whole-lot-less.

I was there to play that guitar. Walmart had pimped a Gibson SG clone for Black Friday, and I wanted to see how it played. Truly a Gibson, too, a Maestro, their Brand X line: “If you’re going to buy a knock-off, we want you to buy our knock-off.” It’s the dollar-store marketing strategy, another distribution channel you sneer at but know nothing about.

I could tell from the picture it was a decent guitar – one pick-up, not two, but a full-length baseball-bat of a Gibson neck and an adjustable bridge. It was a real instrument for the price of a toy.

I missed the Black Friday price, my annual reward for missing Black Friday, but I wasn’t there to buy it, anyway. There’s no one at home to laugh at me for schlepping in another guitar, and even the Everyday-Low-Price was less than a day on the train for me, but it is in fact possible to have enough guitars – at least that’s what I’ve heard.

“I’ve never liked this SG form-factor,” I said to Josh and to the crowd generally. Some little brothers and sisters had squirmed their way to the front, and they proved I was definitely making music by dancing to it.

I had snagged a utility bucket from the hardware aisle and I was sitting on that, upside-down, by the guitars – not many to choose from, and mostly crap. Everything sells as an all-in-one-kit: Guitar, amplifier, strap, even plastic plectra – that’s guitar picks to you – all in one box. They’re not musical instruments, not to Walmart. They’re Christmas gifts. I didn’t trust the amps – or the availability of power – so I had brought my own, battery-powered but with some punch to it.

“Every guitar should be a beautiful woman with a long, thin neck. An SG looks like a demon in silhouette. But that’s why young guys like ’em. More menacing.” The boys all smiled and I knew I was right. “Even so, this is a smokin’ deal.”

I was playing all through this, accompanying my speech, yes, but playing just because I can – dancing in delight with my hands. “I have an old Stratocaster at home. She’s always ready to dance a delicate Tarantelle. But an SG can throb like Thor’s migraine, and young guys like that kind of power, too.”

Every once in a while I could hear a guitar box being picked off the gondola behind me, so it seemed like a good time to double-down.

“I think a solid-body electric like this is the best learning guitar. The action is lower, so you can gain precision with your left hand, even as you’re building strength and callouses. And when you can’t play loud, you can unplug it and play quietly. You’ll hear the strings, but no one else will, but you’ll feel them, too – in your hands and in the resonance of the wood against your chest.”

I turned down the volume so they could hear: At a distance, the sound is tinny and faint, but when you’re right over it, it’s almost as good as an acoustic guitar, but without the echo back from the room.

“But wait,” I said, mocking an infomercial announcer. “There’s more. When you master anything, you master mastery – the kind of follow-through that makes a man a man. But when you master a musical instrument, you learn a new way to talk – and a new way to feel. You can express yourself fully, for a change, and no one can shout you down with vitriol or shoot you down with vocabulary.”

Want me to tell you a secret? There are no decision-makers at Christmas. The merch is going to move, and every dollar and then some will be spent. It’s the brand-specifiers who matter, since they determine which treasures will go home and which will hit the clearance rack after New Year’s Day.

“It’s funny, and it’ll surprise you when you realize it, but it becomes a part of you, like hand gestures or facial expressions. It becomes another way for your emotions and your body to express who you are, and one day you’ll find yourself making music that you are not purposefully composing, it’s just coming out of you, like humming or whistling – but so much richer.”

One of the moms said, “I call bullshit. Nobody can make good music on a cheapshit guitar.”

To that I said nothing, I just switched to Pachelbel’s Canon. It’s quite a bit easier to play than the rock progression I had been doing, but it sounds impressive to the untutored ear. I was playing it flat-baroque, in decomposed chords, but all of this is just Busker music – simple tunes to milk a simple living from simple minds.

To Stingray I said, “Tell ’em how badly I play.”

He smirked, but he wouldn’t say anything.

“He’s too kind. I call my guitar style floppy, sloppy and late. Any one of you kids can play better than me a year from now, if you apply yourself. This won’t be the best instrument you’ll ever play, but you’ll move up as you learn, and this will always be a good travel or practice or loaner guitar. If you take care of it, you can pass it along to your own son, someday.”

Don’t promote the product you want sold, people the world you want it sold into.

To the mom who had spoken up – but to all the moms and to all the boys – I said: “I’m not playing to make music. I’m playing to make conversation, to make connections – to make friends. But when you have a guitar or a violin or even just a harmonica, you always have a friend. You always have someone to talk to, and you always have someone who can speak for you, when you don’t know what to say. It’s a hard world for young men – harder every day. Having a friend you can always count on makes it easier.”

And that ain’t nothing but a lifeline, and it’s sad there has to be one, but it’s even sadder when there isn’t.

Just then Walmart management showed up, in rank order: Short sleeves with necktie, short sleeves with open collar, and blue pullover smock.

Necktie said, “We’ll need to clear this aisle.” He was still working his way inward, so he hadn’t seen me yet. When he did, he said, “You can’t do that.”

“I can’t do what? Test-drive the product?”

“Well,” he said, gathering his wits. “You can’t– You can’t– You can’t demo it.”

Just then another blue smock showed up, pulling a four-wheeled cart. To Necktie he said, “These guitars popped up on my screen, but then they kept jumping up higher and higher, so I thought I’d better get them over here fast.”

Necktie ignored that. To me he said, “Out. Now. Before I call the law.”

I shrugged, saying, “Dictum. Factum.” I could see the confusion surmounting his ire. “Said. Done.” I put the guitar back on the display and handed the bucket to the first blue smock. “That goes back to hardware. And this–” I held up my little amp and its cable. “This is mine. You don’t sell these.”

Necktie was vindicated, but everyone else was looking at him like he just shot Santa Claus. I cannot for the life of me imagine why brick ’n’ mortar retail should be dying.

I said to him, “While we’re leaving, you might call the office and ask how many of these Maestro SG guitars have left the store in the last half hour. I see four – no, five – in carts right here.”

To that he said nothing, just glared at me. If he had any brains, he would have offered me a space of my own and a straight-commission-sales pay plan. Instead he kicked us out. Not the first time I’ve been eighty-sixed – and not from the cheesiest joint, either.

To the boys I offered this: “It doesn’t matter if it’s a guitar or a skateboard or a computer or a broken-down old car. If you master what you do, it will make a man of you. You’re born with everything you need. You just have to cultivate it to make what you want of it. Merry Christmas.”

I was threading my way through the crowd and back to Josh as I was saying that. Timing is everything. By the time I was done, I was clear and we were gone.

I was walking double-quick-time and Josh was hustling to keep up and not asking the question, so I said, “When someone brings up the police, don’t wait around to meet ’em. That story almost never ends happily.”

“What were we just doing back there?”

“I was trying to get through to a kid.”

“Which kid?”

“That’s the trouble. I never know which one. Ask me again in ten years. None of those boys has a father at home, not one who’s doing the job. They are tossed around by this tempest and nobody cares – except to blame them for everything that goes wrong. But if they can find just one timber to cling to, one rock to build a life on, then someday maybe they can be the kind of fathers they never had.”

“And you think this is going to make all the difference?”

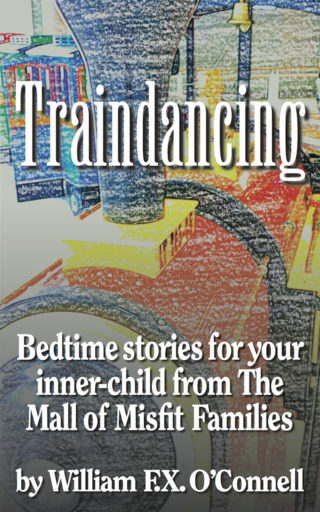

Hope is family. Family is hope.That’s why trains go in circles.Find more Traindancing stories at Amazon.com.

“Is that why you drive that train every day?”

I smiled. “My middle names are Francis Xavier, and I am missionary to the toddlers of Greater Arrowhead. When I have a chance, I try to talk to tweenagers, too.”

He scowled. “What good do you think you’re going to do?”

“What good did it do me to talk to Tegan all these years? What good is it doing me to talk to you?”

No answer.

I grinned. “Which kid did I come here to talk to, Josh?”

He said nothing, and that’s what I like about him best: He knows when to shut up.