What’s better than an ideal? An idol. All belief, no follow-through. What’s even better than that? An icon. If you’ve got a pocket, you’ve got redemption. Now how hard was that?Image by: jay pangan 3

For god so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. (John 3:16)

Here’s a little story, a tragedy in three acts in the briefest kind of synopsis:

Act I. A mysterious stranger comes to a troubled town. Act II. He stands down received wisdom and makes a few fast friends and a vast horde of stout enemies. Matters come to a head and in the final confrontation he wins by losing. Act III. After the stranger is gone the town is on its way to being healed. The end.

You’ve heard that story before, haven’t you? Maybe it was a western. Maybe it was a few dozen westerns. Perhaps a detective story or a space opera or a swashbuckler. Maybe a tale about knights errant besting tyrants or slaying dragons. A scientist who wins over a dubious public with a miracle cure. A scholar who proves an idea thought to be heretical. Columbus, for goodness sake, along with dozens of other great names of history we were taught to remember back when schools taught children to remember.

It’s the story of Socrates, of course, who drank the hemlock rather than renounce his truth. And it’s the story of Prometheus, who was chained to the rock and tormented by vultures for delivering unto humankind the fire of the gods.

And it’s the story of the messiah, Jesus of Nazareth, Rex Judaeorum.

And it’s because of the Nazarene that the story matters to us. There are two significant parts to the story, Acts II and III. In Act II, the stranger – the rebel, the renegade, the revolutionary – commits his heresy and stands by it, an excruciatingly individualistic act. This is the primal story of individualism, and it shows up again and again in the mythology of the earliest forebears of The West. But it is Act III – the healing of the community – that is new with the Nazarene.

We tell this story over and over again. We have been telling it for 2,000 years, and thousands of new versions of it will be produced this year. It is the story of The West. Not the only story, not by far, but it is by far the most common story, and it is the story we remember. Every story we remember, as a culture and as individuals, parallels the story of the Nazarene. The fact is that we shape real-world events, those reported to us and those we live through at first-hand, to fit this mold. This is a song we can sing endlessly, without a score and without accompaniment.

What we do not see, what we do not look to see, is this: The story of the Nazarene, the original and every copy, is a story of human sacrifice.

The story is not: A scholar has an epiphany.

The story is not: A scientist achieves a breakthrough.

The story is not: A knight tests his mettle.

The story is not: A lone hero – a swordsman or a gunman or a laser cannoneer – stands his ground.

The story is: The community is healed by a human sacrifice.

Sacrifice is one of those words that should always raise hackles among thoughtful people. A sacrifice is not a matter of working Saturdays to put the kids through school. A sacrifice is an offering, usually a blood offering, to appease a god. When the politicians say, “We’re all going to have to make some sacrifices,” they are telling the precise and literal truth and you are too kind and too naive to believe them. By “sacrifices” they mean the blood from your veins and the sweat from your brow, and they intend to take it not for your benefit or for anyone’s but simply to take it, to demonstrate their power to demand sacrifices and to appease their lust for symbolic blood. We pride ourselves on our high civilization, but any culture that demands the sacrifice of human lives or the time or the product of human lives is savage, irrespective of its achievements.

And it is in Act III of the story of The West, the story of the Nazarene, that we express our far-from-vestigial savagery. Act II, the story of Socrates, is about individualism. Cyrano stands not high it may be but alone. Act III is about collectivism. Act III is about the community. Act III is about the means by which the collective seizes upon a fundamentally individualistic – egoistic – act and expropriates it for its own benefit. Prometheus stole the fire of the gods not for his own use, not for his amusement, not for revenge, not for spite, not for any reason that began and ended solely with himself. Prometheus stole the fire of the gods to give it to the community, which had done nothing at all to deserve it.

The Nazarene, so says the Church, so says John 3:16, did not permit himself to be murdered for his own reasons. He refused to explain himself to Pontius Pilate and he refused to kowtow to King Herod. He refused to call himself King of the Jews, and, like Socrates before him, he refused to renounce his truth. But, the claim runs, he didn’t do this for any reason that began and ended solely with himself. Instead, he permitted himself to be sacrificed – killed to appease a god – so that the community could have life unending, which it had done nothing at all to deserve.

Act II is about an individual who corrects an error or an injustice by a selfish act of courage. Act III is about a community usurping the achievement of that individual and conferring upon itself – at his expense, often at the expense of his life – benefits it has not earned and does not deserve.

Act III is the true kernel of the story of The West: Individuals sacrifice their lives for the sake of the community and we revere their greatness by behaving nothing like them. This is what we are. Tragically.

And the story of The West is one we must tell and must have told to us again and again. We, the herd of us, are the god we must appease with our blood sacrifices, and like every savage god we require new sacrifices to be made to us. We can sate our bloodlust with an execution every now and then, but a blood sacrifice cannot be made of someone who has sinned; we sacrifice virgins, not whores. To be an appropriate human sacrifice, the victim must be like the Nazarene, Agnus Dei, the sacrificial lamb of god. The victim must be someone who not only does not deserve to die, but who deserves more than anyone to live. A human sacrifice seeks to reward the undeserving en masse by delivering a particular and excruciatingly unjust penalty to the very best among us, an individual and an individualist.

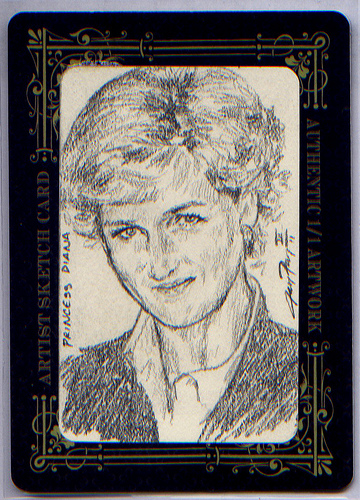

I’ve been thinking about this in the context of Diana Spencer, holder of numerous titles that are, thank the goodness and wisdom of humans we did not sacrifice, illegal in the United States. She wasn’t much of an egoist and, to the extent that she stood for anything, she didn’t stand very tall. But her silences must have surpassed eloquence, judging from the volumes that have been read into them. And if she was not that mysterious a stranger, the town she came into was troubled enough to make up for it.

Diana Spencer died in an automobile accident. She wasn’t wearing a seatbelt, and the car was virtually destroyed. Despite what you might infer by watching television, she wasn’t actually flogged before Pilate and Herod, then forced to drag a cross up Calvary Hill while wearing an elegant crown of thorns. But amid the media feeding frenzy about the evil nature of media feeding frenzies, a new story is emerging.

What’s it about? You can guess, can’t you? We only remember one story, after all.

Diana Spencer died by accident, but the press and the public are turning her into a Christ-like human sacrifice nevertheless. She is to be the blessed martyr who gave her life to save the monarchy. A new monarchy. A better monarchy. Touchier, feelier, more in tune with the craving of the masses to be loved unconditionally in appreciation for the accomplishment of absolutely nothing. She died so that the community can claim to have been healed by the elixir of her blood.

Saving the monarchy is assuredly a benefit of dubious worth. Monarchy is in fact a crude pantomime of the story of human sacrifice, the story of The West. The monarch – or the politician – gives his life to the community, it is said, but not only does he not lose his life, he prospers better than anyone. Prometheus was fed to the vultures and the monarchs and politicians warm their hands by the fire.

The fatal conceit of The West is that savages are stupid. Alas, it’s true. We are.