Mostly vampire bait is an incipient vampire, after all. Miraculously dyschristened at the fount of new age wisdom, feeding life to death to become the death that feeds on life. And I walk among the walking dead listening to the words nobody said. But there are times when silence just won’t do, even if words won’t do any good either. And everybody knows: Everybody’s gotta take a side.Photo by: swong95765

May 24, 1997

Mostly it’s my job to hear the words that are not said. I crave the nattering chickadee’s chatter, so it must seem, but every little squalid scene that attracts my attention begins in a raucous cacophony of silence, and it’s the pronouncements no one dares to utter that ring so ragingly in my ear. I listen to the pauses, the omissions, the captured breaths that cultivate lies and poison precious truths. I write what does get said, because that’s what there is to write. But it’s what doesn’t get said that matters.

And it’s a job I can get enough of, sometimes. I was sitting in a Taco Bell, waiting out the always-late number seven bus in a space somewhat less depressing than the bus-stop outside. But it wasn’t much less depressing, because the cacophony of silence was too loud even for me.

I was watching an incipient divorce, a very married couple silently not having a fight over lunch. He was eating big and pretending nothing was too terribly wrong. She had nothing, not even a cup of water; she sat there folding herself into thirds, lengthwise along the spine, so as to simulate disappearance. He was eating large and moving large and ignoring her with a large performance of an immense indifference, and her face, at first just pouting, turned a whiter shade of sulk. He was trying to be just anybody, any old body at all, and she was trying with all her might to be nobody. I wanted to slap them both.

Instead, I got up and strode out to the bus-stop. Kinda cool, kinda dry, kinda sunny and the air smelled pretty good. But I’m impossible to please, I guess: There was a sullen little creepette out there with a book and a boombox, and I was bugged by her without really knowing why.

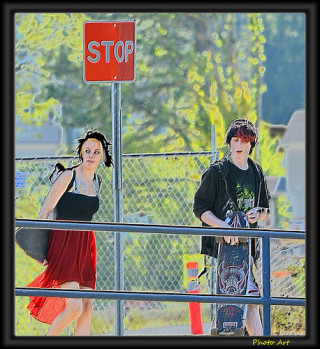

Vampire bait: Her skin was not white but gray, leached of every hue of vitality. Her fingernails and her lips were painted black, and her sunken eyes were done up in a garish purple. Her hair was dyed jet black except for one shock of shocking pink; it was cut off abruptly in a brutal pageboy. I have no guess what her hair color might have been before she dyed it, except that I know for certain it wasn’t blonde; blonde-headed women never dye their hair any color except blonder. She had four or perhaps five tiny rings in each ear, and three in her right nostril. She wore a sleeveless black body-stocking and, incongruously, a pink seersucker babydoll dress, much too short. Over it, she wore a bulky gray sweater that had made the acquaintance of more than one moth. On her feet were a pair of big, clunky black Doc Martens boots. The body-stocking was infested with snags and runs, and everything she wore was dirty and smelled it.

Even the damned boombox was black. But they all are, of course, except for the ones that are yellow and look like they ought to be submersible or the ones that are pink and are never seen in the presence of anyone older than ten or younger than forty-two. A CD was playing, programmed to play one tune over and over. It was “Everybody Knows” by Leonard Cohen, the National Anthem of the Vampire Bait Nation.

Everybody knows that the dice are loaded.

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed.

Everybody knows the war is over.

Everybody knows the good guys lost.

Everybody knows the fight was fixed:

the poor stay poor, the rich get rich.

That’s how it goes.

Everybody knows.

The book was something like, “How to Hex Your Ex,” a fount of new age wisdom such as used to be found over the chewing gum in the checkout line at the supermarket: Tiny little books bound with staples and selling for fifty-nine cents or less. But it’s a whole new age for new age wisdom, and now the books are large and perfect-bound and sell for fifteen dollars or more. Distressing education news on all sides: Even gullible semi-literates aren’t as smart as they used to be…

From up the street there came shambling the epic urban lumberjack, every bit the spittin’ image of Paul Bunyon, except that he was short and scrawny and maybe just a little bit effete. But he had the boots, by gum!, big, clunky work boots, unlaced, with the laces dragging on the sidewalk. And his denim trousers were surely big enough for Paul Bunyon, with room left over for Babe the Blue Ox. And, O!, what a shirt he had: It was no mere Highland plaid flannel shirt, it was a Highland plaid flannel shirt with quilted nylon insulation at the cuffs and collar. His hair was razored all up the sides, and even on top it would have to be measured with calipers. He had a wispy little moustache, barely there at all, and a goatee to remind us all of the bygone days when Paul Bunyon was a regular character on Dobie Gillis.

But even in cutting such a ridiculous figure, there was something about his that was not quite vampire bait, something chipping its way out of that eggshell of youth that might yet be a coffin. Or so it seemed, anyway. He didn’t care enough to lace his stupid boots, but he did care enough to square his shoulders, and that’s a start, I suppose.

“And there she is,” he said as he came upon her. “Making her daring escape in her lightning fast getaway bus.”

She said, “How did—,” then cut herself off. How did you know I’d be here? How did you know it was me? How did you know? To speak would be to confess, but, of course, the silence confessed just as fully.

“Jeez!” he said. “You smoked three cigarettes while you were there! Ugly little white cigarette butts with ugly black lipstick marks. God knows I’ve seen enough of them.”

She said nothing, just stared at him with a jowly glare.

He shook his head slowly. “I never thought you’d rip me off. You dumped me, and I guess I knew you weren’t the girl of my dreams, anyway. But I didn’t think I had to ask for the damned key back. What’d you do, go through all the drawers looking for cash? A three cigarette search, and all you could find to steal was my stereo…”

The sweater was bunched up in the crook of her left elbow and she picked at it a little. She had a tissue knotted up in a tight little ball in her left hand, and she dug around in her nose with it. She sniffled.

“Don’t just sit there. Say something!”

“What do you want me to say!?” she demanded.

He shrugged. “What can you say? ‘I’m sorry’? What good would that do? What would it mean? You can’t steal unless you’re a liar first, and who cares what a liar says?”

Her face took on a hurt expression, more hurt than the sulky woman in the Taco Bell.

“I get it,” he said. “Now it’s all my fault. You live your bullshit life, and maybe that’s wrong and maybe it isn’t. But if I call you on it, I’m the bad guy, and whatever you did was just tit-for-tat, tit first.” He laughed, a hard and bitter laugh.

He said, “You wanna know who’s the idiot? I’m the idiot! Ever since high school I’ve been listening to more and more elaborate excuses for evil, and, if I haven’t gone along with them, I haven’t shot ’em down, either. Your inner child and your higher power and your spirit guide and your unhappy childhood, those are all just bullshit excuses for the worst kind of crimes. You want it both ways. You want to get over on everybody, but you want to seem like a decent person. Well, there’s my stolen ghetto-blaster, and you don’t seem like anything but a goddamned thief!”

Her face was torn by an animal’s rage. “And what about you? What do you seem like!?”

He simply smiled, and the smile was answer enough. He said, “My father has a plaque behind his desk. It says, ‘Be and not seem.’ That’s a quote from Emerson. I’ve been thinking about it a lot, lately.”

“And since when do you have such great respect for your father…?”

He smiled again. “In all the years I’ve known him, my dad’s never ripped me off. He’s never ditched me in a club or lied about me to my friends or put cigarette burns in my clothes. He’s never wanted anything but the best for me… I wish I’d been as good to him as he’s been to me…”

She shook her head, hard and fast.

“Shake it off, shake it off, shake it off! That’s what the third base coach used to say when we slid too hard or took a ball in the chest. He meant, ‘Do something stupid to forget the pain.’ Shake it off, shake it off, shake it off! It’s what you do when you’re telling yourself a lie.”

She glared at him again, picking at the crook of her elbow.

He said, “You’ve taught me more about lying than I ever wanted to know. It’s not me you lie to, not really, and it’s not anyone else. It’s you… You are the person you have to fool. You can lie to me or to some teacher or to your boss or to the landlady, but that’s nothing, just words. But the lie behind the lie really matters, the little war you have to make on your own mind. You have to pretend that something you know is true isn’t, and you have to pretend it all the time, even though you know it’s all an act. You have to pretend you aren’t what you know you really are. Not to con somebody else, but because you can’t stand knowing what you’ve become. And when someone gets too close, when the fraud threatens to become too obvious, you know what you have to do…?”

She shook her head, hard and fast.

“Shake it off, shake it off, shake it off!” He laughed, the joyless laugh of an empty triumph. “Every one of those damned excuses for evil you grow in your garden of pain, every one of them exists so you can pretend that your problems are someone else’s fault. So you can excuse yourself by blaming somebody else. It’s me or the teacher or the boss or the landlady, whatever happens. It’s not your fault, not ever. But the truth is, everything that happens to you happens because you’re at war with your own life, at war with your own mind. All those bullshit philosophers in all those bullshit philosophy classes – you are what they produce, a crumpled up ball of human garbage…”

She didn’t look at him, not even to glare. She snuffled into her tissue and picked at her elbow.

Quick as a cat, he grabbed her left hand and skinned the sweater up her arm. In the crook of her elbow there were five dark, button-sized bruises. Each one of those bruises had a dozen or more button holes, I knew.

“Jesus Christ…” he said. “That explains why you ripped me off… Found yourself the perfect excuse, didn’t you?”

She rose to her own defense. “It’s not what you think!”

“It’s exactly what I think. If you refuse to live, it’s the same as being dead. That’s what everybody knows.”

She shook her head, hard and fast.

He scoffed, a short puff of air through his nose, barely a sound at all. Silence lies with glib facility and silence speaks the truth with pristine and perfect eloquence. He said, “Keep the stereo. Call it tuition. It was a bargain.”

She pulled her knees to her chin, folding herself in fourths at the knees, at the waist, at the neck. She was becoming nobody, and, as he strode away, he seemed to me to be becoming somebody. Not just anybody, but somebody definite, stand or fall. Not vampire bait at all, not anymore.

She looked up at me, planting her chin on her knee. “What’re you looking at?”

Mostly vampire bait is an incipient vampire, after all. Miraculously dyschristened at the fount of new age wisdom, feeding life to death to become the death that feeds on life. And I walk among the walking dead listening to the words nobody said. But there are times when silence just won’t do, even if words won’t do any good either. And everybody knows: Everybody’s gotta take a side. I stood up and brought forth sound, telling the brutal, literal truth. I said: “Nothing.”