Authors die, but their ideas need not. I am vain enough to declare that I lack the everyday flavor of authorial vanity, but I more than make up for that with the other kind. There is no place for me in the bookstore — and, for god’s sake, why would there be? But there is room for my words on the wall of a bus, and it could be I have etched my way into stone, somewhere, by now.

June 2, 2013

This is a story about a story, so fasten your seatbelt. At any moment, we could be plunged three layers deep in narration, like that daredevil Emily Brontë, who first taught the English-speaking world how to do this job.

Here’s what happened: I was in Houston for a while last Summer, about which more probably never. I got around by bus, easy enough to do for anyone who likes to wait and walk. One sweaty afternoon I sat down on a bus and to my right, scratched into that semi-indestructible stuff they use to line buses, were these words:

Do your worst. I will not kneel.

I wrote that, a long time ago, in a story called Anastasia in the Light and Shadow. It’s my own favorite of the Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie stories, and I know other people love it, too. There really is an Anastasia, so you know. The story is all mine — the world is my sock puppet — but that little girl must be old enough to vote by now.

But it’s the scratching in the wall that’s interesting to me. I think I may have less authorial vanity than is common, plausibly because I have less reason for it, and less use. If I make the mistake of counting my money, I suffer a long contemplation after a quick calculation; it’s enough to ruin my whole day. But the words of the prophets are written on the subway walls — or bus walls in cities more suburban — and that is success as almost no writer ever has it.

When I was a young guy in Fun City, I got around town, for the most part, on the Seventh Avenue IRT — that’s the 1, 2 and 3 trains for all you tourists. You step up to the platform to wait for the train and to your left will be a cast-iron girder, rough as an alligator when it was poured but smoothed and sculpted and rounded by decades’ of high-gloss latex paint. And scratched into that paint, just at eye level, will be this:

Pray

On every girder. On every platform. In every station. Hundreds of girders, maybe thousands, all inscribed “Pray.”

Do you want to dismiss it? Are you at your ease only when the world is small and stupid and undemanding? Yes, someone has OCD — maybe several someones. But the effort it takes to scratch those four little letters into hard, thick-slathered paint, and then to do that again and again, girder after girder, day after day, station after station… If you’re looking for commitment on this earth, you found it.

But normal people aren’t like that. They work, they play, they veg out in front of the idiot box. They read, but not seriously, as anyone can discover by hurrying down to the bookstore before it shuts down for good.

Once in a while someone gets lucky, and he reads a few words that stick with him, and he will quote them back to his family and friends when the moment seems right. The author will have found a space inside that reader’s brain, and they will be married together in that small way forever.

Rarer still, it can happen that a person will read something that will change his whole life. It can be nothing or anything, and the author may not even know which of his words were the catalyst, but a few simple words on a page can help to remake and redeem an entire human life. How awesome is that?

And even still more rare, a reader will be so moved that he will take a pen or a marker or the bent tine of a fork, and he will scratch the words that have altered his life forever in a place where someone — anyone, everyone — can see them.

This is the authorial act on that reader’s part, to spread those few words as far as he can, to speak them not to anyone in particular, but to shout them out to a world that needs to know this. It’s communication — not so much suasion as a simple clasping of hands — but it’s benevolent magic, too: The reader is transported to a newer, cleaner, better life by the act of inscribing those words into the substance of the universe.

This is success for an author. Money and acclaim are just so much toilet paper, here today, gone tomorrow — and good riddance. Emily Brontë owns all of your mind and none of your money, and you never even think to criticize the convoluted story structure of Wuthering Heights, so enthralled are you by Heathcliff and Cathy and that pansy-ass beta loser next door.

I want to write memorably. If you talk to a normal writer, you’ll hear all kinds of ornamental bullshit about means and modes and goals and objectives. I want to write memorably. The words you don’t hear in that sentence, because you’ve never learned to listen for them, are these: “To myself.” I want to write memorably to myself.

If you remember something I’ve written, so much the better. If I write a few words that end up changing your life for the good, better still. If I push you to the point that I pushed some enraptured soul in Texas, a point where you are changed so much that you must embroider the universe in celebration, even better. But I’m not doing any of this for you. I’m doing it for me. I want my words inscribed in my brain, where I can see them, like a trail marker, forever.

The conquistador Marcos de Niza chiseled a mark into the stone of South Mountain, south of where Phoenix is now situated, when he and his troops where there in 1539. Who is Marcos de Niza? He’s a few paragraphs here and a long footnote over there. He’s a high school in Tempe, not far from South Mountain. He’s nobody. But that mark of his is coming on 500 years old, and it could still be there 500 years from now.

Authors die, but their ideas need not. I am vain enough to declare that I lack the everyday flavor of authorial vanity, but I more than make up for that with the other kind. There is no place for me in the bookstore — and, for god’s sake, why would there be? But there is room for my words on the wall of a bus, and it could be I have etched my way into stone, somewhere, by now.

I write for myself, so I am always fully compensated for my efforts. But since Houston I am aware that I actually stand a chance of standing with Miss Brontë, to be paid best by readers who only discover my writing after I am dead. Readers who will forgive my ignorance and my infelicities and love my words at their best, love the very best ideas I have unearthed in a lifetime of quarrying.

I like that I get to talk to those readers. I like that I get to talk to you. But, really, I just like to write, to tell the truth as beautifully and as memorably as I can. If that makes your life better, I’m glad. But I know it makes my life better, and that’s what I get from my writing.

Can I scratch those seven words

Do your worst. I will not kneel.

into the walls of the universe? Seven hundred more? Seven thousand more? Seven million more? None at all?

It doesn’t matter. This is how I live my life, and this is how I make my life better every day. If you read along, if I help to make your life better, that’s wonderful. But this story about a story could be the lynchpin event in my life, the one I’m always looking for in your life.

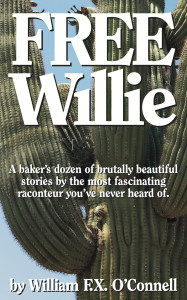

This is one of the stories collected in the free book FREE Willie. Get yours today!

Fiction is for saps, but if you’re not a sap for your own fiction, you’re the worst kind of sucker. Give the people what you think they want and you’ll end up with nothing, stacks and stacks of toilet paper. But if you give your self what you want, if you say the words you need more than anything to hear, and then you share those words with anyone willing to live up to them, your ideas just might live forever.

And how awesome is that…?