But the main job of being a father is simply being around. I’m not congratulating myself for what I did with Xavier, because I knew it was temporary. He didn’t have a father all of a sudden, he just had a weak little prosthetic, and that only for a while. But I taught him what little I could of the manly art of manliness, what little I know. A little bit of swagger, not too much. A little bit of strut, just a touch. A little bit of courtliness, rough around the edges. A little bit of mischief, creeping through the hedges. A man rolls up his sleeves and gets to work, and you can say it with a smile if you can’t say it with a smirk.Photo by: Kenneth Lu

March 13, 1996

“Madre de dios…!”

Mrs. Marquez said that, and it seemed a fair estimate to me. Everywhere we looked in the overlit room we saw things of wonder and beauty and uncontested menace. Despite the din, I heard myself groan, and I wasn’t utterly sure I’d done the right thing. Walking through the valley of the shadow of death in a grade school cafeteria is one thing. Pushing an underfed eight-year-old boychild ahead of you is another.

The road I walk is the path that separates the straights from the crooks, the pencil-fine line that splits the people we call “decent” from the sneaks, the freaks and the side-show geeks. I have a scruple or two, painted and waxed, so I don’t quite fit in among the bungled and the botched. And yet I do have an itinerary, and I don’t have much of an agenda, so the quality folk are never dismayed to see the back of me. Neither fish nor fowl, always on the prowl, quick to resign from any community that would even consider having me as a member. This is the life I’ve chosen for myself, after all, and I’d be daft to beef about it.

Still, there are Other Matters to consider. Among them: I’ve been nineteen-years-old forever, but I’ve been nineteen for a lot of years. I’m making a buck or two more than I ever have before, and staying in one spot a day or two — or a week or two, or a month or two — is not only more desirable than it ever was before, it’s suddenly financially possible where it never was before. Plus which, I don’t love the cold and I do love the sweet smell of orange blossoms. And to make a belabored excuse slightly less laborious, I’ll just come out with it: I hung out in a half-big town halfway from nowhere for so long that I got myself well and truly hooked in a scheme straight out of the handbook of the straights.

I was renting week-to-week at the Orangeview Estates, and my next-door neighbors in the tiny four-plex were Mrs. Marquez and her scrawny little manchild, Xavier. Xavier was a Cub Scout, and I helped him enter the Pinewood Derby. No kidding. Not quite singing hymns and selling Amway, but damned near it.

Orangeview Estates promotes itself as an apartment complex, but it’s actually more like a crude motelization of superannuated picker housing. Picker housing is wood-frame and stucco, because you don’t have to import labor to build wood-frame and stucco, and it’s four-plexed to keep the plumbing — such as it is — cheap. Mostly the real pickers live in their trucks, because they go for the winter produce before the citrus comes in and move on to the summer crops after the citrus plays out and because their trucks are rent-free. The picker housing used to be owned and maintained by the growers, but by now a lot of it has been sold to become palatial family residences available by the month, by the week or by the day, cash in advance if you please.

If you imagine a very seedy motel room and then cross that with a run-down shack, you’re imagining a home much nicer than the Orangeview Estates. On the other hand, the rent was dirt cheap, the aroma from the orange groves was heavenly and the irrigation and the shade from the orange trees kept everything nice and cool. Back on the first hand, the neighbors mostly ran from unsavory to completely gruesome. There are half-big citrus towns all across the desert, and there’s nothing to do in any of them except work for the growers. Year-round work is rare and the pickers move along. The people who stay have nothing to do but make trouble, and they’re good at it. As an expression of tacit racism, the desk clerk had put me in among the respectable folk at Orangeview Estates.

To my left were the Sandovals, an ancient couple who went to mass every morning, then tended the church and rectory grounds all day, then went to confession every afternoon, then came home and fell asleep before they could possibly have time to sin or even think about it. Surely they are destined for the highest pinnacle of heaven — unless they are cast to the beasts for wasting so much of god’s time.

To my right were Mrs. Marquez and Xavier. Very much “Missus” Marquez. The only times I saw anger in her eyes were when someone called her “Ms.”, or worse, “Miss”. Every once in a while, some old crone would wonder too loudly where Mister Marquez might be found. When that happened the anger would still be there, but Mrs. Marquez would have her chin so high you couldn’t see it. She was in Orangeview Estates, but she was not of it, and she never forgot that simple fact, and she never let anyone else forget it, either. She was a cook in the home of one of the larger growers and she carried herself with a mien that would not have looked at all out of place in fifteenth century Madrid.

To the right of Mrs. Marquez was the Hernandez family, Hugo and Juanita and five giggling daughters, all crammed into a space that seemed to me to be too small for my one small self. Hugo knew that Xavier needed a father’s guidance, and I think he might have been a little hungry for a son, as well. But Juanita had daggers in her eyes, and she made it plain in a hundred non-subtle ways that she would be happy to lend Hugo to Mrs. Marquez as soon as the mysterious Mr. Marquez evinced himself and made that generosity unnecessary.

And so I’m sure that’s why Mrs. Marquez turned to me with the problem of the Pinewood Derby. I might have looked straight and respectable to the management of the Orangeview Estates, by comparison with most of the tenants, but this is not a flattering evaluation. And there is no one who has talked with me for five minutes who will confuse me with the decent folks. Merely being the gringo in residence at the Orangeview Estates raised eyebrows, even among the crooks. The boy had been walking with me every afternoon, but I hadn’t bowdlerized my speech to protect his frail sensibilities. I was telling him the straight and brutal truth, which I can be counted upon to do with everyone, and I hope I was doing him some good in the long run. But it might not have come off sounding so good in the short run, especially to a mother who couldn’t quite figure out how to cut the cord. I had no idea how much of our conversations he was carrying home to his mama. Couldn’t have been too bad, I guess, considering.

In the citrus towns, in the winter produce towns, in the cotton towns, in all the little half-big agricultural towns of the desert, the growers and their year-round gringo care-takers account for about ten percent of the population. But they control everything. In situations like that, we expect to find lousy public schools and excellent private schools. That’s the way it is back East, up North. But the people who settled the deserts had great faith in the public schools; the public schools and federally-subsidized irrigation are what made ’em what they are today. Since the growers are compelled to pay for public schools, and since they control them anyway, there’s no cost to them to sending their own children to the public schools. You can take it as a rule of thumb that the public schools will be excellent wherever they are controlled utterly by people with money who know what they want.

Certainly that was true of Xavier’s school — at least for the children of the growers and their year-round gringo care-takers. The schools had an academic track that was as good as any you’ll find in a magnet school in a big city. They also had a barrio track for los niños de los barrios; you didn’t learn much, but there was no threat you’d be found truant, especially when the fruit was full on the trees. But if Mrs. Marquez was not in the aristocracy, she was most certainly of it; she bulled her way past every obstacle to ensure that Xavier was enrolled in the academic track, not the barrio track. He was much better prepared than the gringo children, since she leaned all over him at home, but it was her persistence, not his preparation, that won him his place.

It was the right thing to have done, but sometimes the right thing comes at a high price. Xavier is short and thin and he wears glasses. His mother makes him wear dress slacks and leather shoes to school, and blinding white shirts and neckties. He has an immense vocabulary and a painstaking way of speaking. He can explain anything to anyone, and he will happily do so, with or without invitation. We all know how things work, and so we all know that Xavier couldn’t be asking for it any better if he had a flashing neon sign on his forehead that said, “Asking for it!” The mildest taunt I heard was, “Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-vee-air!” I’m sure more and worse was said out of any adult’s earshot.

And that’s the way things are, not an excuse but a recognition. But I don’t always much like the way things are, and that’s why I started inviting Xavier along on my walks. I didn’t expect to change much, and in truth I don’t ever expect much to change. But nothing changes if you leave it alone, and everybody’s gotta take a side. Thus does Brother Willie put one toe over the line into the land of the straights.

The Pinewood Derby thing kind of slipped in there sideways, and it wasn’t until much later that I realized just how much Mrs. Marquez had staked on my unreliable tutelage. On its face, the Derby is pretty much nothing: Cub Scouts build and race small wooden cars. But what it’s really about is a comprehensive introduction to manly virtues. Our mamas teach us and teach and teach us until we move away and still they keep after us. But what they teach us are their ideas of virtue: wash your face, brush your teeth, clean your room, pick up after yourself — and phone home. The Pinewood Derby strives to impart self-reliance and foresight and application and persistence and intense competition and good sportsmanship. It’s also supposed to be fun, but, clearly, the primary objectives are didactic.

When Mrs. Marquez showed up with little Xavier and the Official Pinewood Derby Racer Kit, I was more than a little dubious. I like those manly virtues just as much as the next guy, but I wish they were a little more portable. Also, I silently cursed Señora Juanita Hernandez and her stupid jealousy; surely this was right up Hugo’s avienda, and he’d probably be good at it, besides. But, play or fold, the cards you’re dealt are the cards you’ve got, so I agreed to read the rules and give it some thought.

The rules were pretty clear: fathers — or those who play them on TV — were consigned to a strictly advisory role. The racer was to be built by Xavier, and I was to limit myself to consulting with him and, in a pinch, lending a finger or two. That didn’t seem too hairy until I talked things over with Mrs. Marquez. Her rules were a little more stringent: Xavier was not to use knives, saws, chisels, drills, files or power tools. I explained to her that the racer kit consisted of a block of pine, drilled for the axles, and some little plastic wheels; without tools, Xavier would be racing an unadorned slab of wood. Her resolution was monolithic and I couldn’t fathom how the school board had managed to hold out against her. Finally she agreed to let Xavier do whatever damage he could to his block of pine with sandpaper. I didn’t tell her that sandpaper can cause nasty abrasions. And neither her English nor my Spanish were good enough for me to get across the idea of emasculation, not that it was really my place to bring it up.

Anyway, daily progress reports about the car became a part of the fragile web of intimacy I shared with the boy. He busted his butt on that racer, and it showed. Pine is a soft wood, and coarse sandpaper puffs it away fast. But “carving” with sandpaper is a serious proposition; it’s an art Xavier essentially invented for himself, since everyone else carves with knives and saws and chisels.

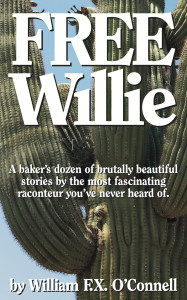

This is one of the stories collected in the free book FREE Willie. Get yours today!

A father is the provider, his most important job. If he neglects it in order to preen as an ersatz mommy, the children suffer. A father is the moral leader, obliged to take it on the chin again and again; that’s how children learn how to take it on the chin. A father is the defender, the one who confronts the burglar when mom and the kids are hiding under the bed. Fathers are everything we claim to admire when we use the word “manly” and everything we affect to despise when we use the word “male”, but, at bottom, fathers are not mothers. We need mothers to do what mothers do, and we need fathers to do what fathers do, and when children are denied one or the other, they suffer. You won’t read this in a women’s magazine, and you won’t read it in a men’s magazine unless it’s tattooed into a well-tanned navel. But it’s the truth.

But the main job of being a father is simply being around. I’m not congratulating myself for what I did with Xavier, because I knew it was temporary. He didn’t have a father all of a sudden, he just had a weak little prosthetic, and that only for a while. But I taught him what little I could of the manly art of manliness, what little I know. A little bit of swagger, not too much. A little bit of strut, just a touch. A little bit of courtliness, rough around the edges. A little bit of mischief, creeping through the hedges. A man rolls up his sleeves and gets to work, and you can say it with a smile if you can’t say it with a smirk.

One day we were out walking and Xavier led me to a bitch with a new litter of pups. Xavier had a thing for puppies and I had the idea that it was a point of contention between him and his mother. The dogs were down in the little light-well of a basement window, a tight fit but defensible. The runt of the litter kept getting pushed aside, pushed aside, pushed aside, all the way down the line of teats. He’d scramble over the bodies of his brothers and sisters and try to worm his way back into the fray, but he just got pushed aside, pushed aside, pushed aside, again and again and again. I pointed it out to Xavier, because, frankly, I never pass up an opportunity like that.

“They’re always going to treat him that way,” I said. “He’ll always be the littlest, and because he is, he’ll always get less milk. Even after they’re weaned, the bigger dogs will still push him around, just because he’s small. He’s lucky he’s a dog. Someone will come along and decide he’s so, so cute because he’s so tiny, and he’ll get adopted. In the wild, he’d be a sitting duck.”

“Why doesn’t he do something?” Xavier asked.

I shrugged. “He’s a dog. He can’t think. He doesn’t know why he’s always getting pushed around, and he can’t think of anything else to do. If he could think, it would be a different story.”

“If he could think he wouldn’t have to get pushed around.”

“He doesn’t have to. He just does. If he could figure out the problem, he could solve it. Just like you can, when you figure out a problem.” I write children’s stories for adults; writing children’s stories for children is child’s play.

Another day, another walk, he said, “I need a name for my car.”

Proving my mastery of witty repartee, I said, “Huh?”

“My car. All the kids name their cars and paint the names on the sides. I keep trying to come up with a name, but nothing seems right. Not yet.”

“It’ll come.”

“I guess so…”

We had wandered pretty far from home and I didn’t like the looks of the neighborhood we were wandering into. There was a frisky little hound up ahead of us, and I knew Xavier wanted to go commune with that dog. I shook my head. “Not that way.”

“Why not? What street is this?”

“Via de los lobos,” I said.

“How do you know? I don’t see any street sign.”

“I know the signs, Xavier. This is the way of the wolves. This is no way for you to go.”

He snorted. “You sound like my mother.”

“I sound like my father.” I looked down the via de los lobos and saw the squalling babies — naked but for dirt and snot — and the dead cars and the broken glass and the broken lives. I said, “I’d like to chase away all those wolves and tear down all those hovels and build one big house down at the end of the road, a hacienda for your mother and for everyone who works as hard she does. I’d name this street via de las aguilas, and you and I could put a big sign right on this spot.”

“What would it say?”

I swept my hand across the sky, painting the words in wide, sweeping arcs. “Via de las aguilas. Why crawl when you can soar?”

Xavier laughed at that, but I knew he wasn’t laughing from mirth.

About a week before the Pinewood Derby we were out walking on a day that was cool and cloudy, dank even. But the orange blossoms had come in full and rich and sticky, and I just wanted to walk and to breathe, to bask in a perfume sweeter than any made in France. Xavier was still puzzling about what to name his car and I was worrying about my place in his life and somehow or another I managed to say, “Xavier, do you know about destiny?”

He gave me a smirk that I am quite sure irritates the crap right out of his classmates. He said, “Destiny is fate. To be destined is to be pre-destined, ordained by god and unavoidable.”

I nodded. “That’s what the dictionary says. But that’s not what people really mean when they use the word. Nothing that people do — nothing that matters, anyway — is unavoidable. And if there’s a god, he sure isn’t ordaining everyone’s thoughts, words and deeds. But if destiny doesn’t mean ‘unavoidable’, what do you think it means?”

He smirked again. “If it doesn’t mean ‘unavoidable’, it doesn’t mean anything.”

I smirked back. “Have it your way.” I walked and smelled the orange blossoms and waited the little snot out.

“Well…?” he finally said.

“Well, what?”

“Jeesh! What do they mean by destiny?”

I could have toyed with him some more, but I didn’t. “Well, looked at one way, they mean nonsense, just like you said. But if they mean nonsense, then the implication is that the things people do are simply random. If they’re not unavoidable, they must be causeless, right?”

“…That doesn’t seem quite right…”

“Give the man a cigar!” I said. “Who controls your actions?”

“…I guess I do…”

“Give the man another cigar! God doesn’t control your actions, and your actions aren’t random, like the toss of a coin. You control your behavior, guided by an idea of who you are and what you do and don’t do. When your mother says, ‘It’s my destiny to raise a good son,’ that’s just an idea, not fate. When Hugo Hernandez says, ‘It’s my destiny to provide for my daughters,’ that’s just an idea, not fate. When Roberta Sandoval says, ‘It’s my destiny to bring glory unto god,’ that’s just an idea, not fate.”

Xavier pushed up his glasses. He said, “But an idea’s just an idea. You can change your mind whenever you want.”

“Sure can. What happens if you do?”

He scoffed. “What? Nothing?”

“Think twice. On the via de las aguilas, they say, ‘Hard work always pays off.’ On the via de los lobos, they say, ‘Hard work never pays off.’ Hugo Hernandez works hard, and sometimes it pays good, and sometimes it doesn’t. Your mother works harder than anyone I’ve ever known, but it hasn’t bought her that hacienda. But Hugo and your mother and the Sandovals live on the via de las aguilas because they believe hard work pays off. Not because it always does, but because they believe it will, if not today then later, if not for them then for their children. What happens if they change their minds?”

He said nothing, just pulled at his chin.

“Via de los lobos, Xavier. It’s not one or the other, not right away. But if you’re not trying to soar, you’re trying to crawl. In life, you have to pick a road and walk it, and destiny is the name we give for the destination we’ve chosen. It’s a choice, an idea, and you can change it at any time. But you can’t pick the via de los lobos as your destination and expect to find yourself on the via de las aguilas.”

He stuffed his hands in his pockets and we walked and walked. Finally he looked up at me and said, “What’s your destiny?”

“Balls first.”

“What!?”

“Balls,” I said. “Cojones.” I pointed at my crotch just to leave no doubt. “Balls first through the universe. If you want to mess with me, I’m not holding anything back. I won’t cower, I won’t cringe, and if you manage to kick me, I won’t give you the satisfaction of the smallest wince. I walk. That’s what I do. And I walk balls first.”

He laughed and laughed, and after that he giggled. I walked balls first through the orange groves and wallowed in the scent of the blossoms.

“I just figured out what to name my car,” he said.

“So tell me.”

He scrunched up his face in indecision. “No. Not yet.” He laughed diabolically.

Oh, great, I thought. He’s going to name his damn car “Balls First” and his mother is going to cook my cojones. I said, “Fine. Keep your secrets.”

He smiled a smug little smile. “I think I will…”

I went to pick them up on the day of the big race, and that was when Xavier finally showed me his car. Basically, it looked like a block of wood that had had all of the edges and corners rounded off by sandpaper. There was something clearly resembling a cockpit in the middle, and although it was as big and as boxy as a police cruiser in a thirties gangster film, it was beyond all doubt a car. The paint job was extraordinary, cobalt blue with orange and yellow flaming racing stripes. Astride the cockpit, where the doors would be located on a real car, the car’s name was painted in yellow with orange detailing: “Xavier’s Destiny”.

And I cursed myself for having such a big mouth. “Xavier’s Destiny” is a fine name for a car that wins, but what about a car that loses? We draw conclusions about life — about ourselves, about the universe — from hopelessly incomplete data. This is irrational, I suppose, but it’s what we do. It’s what we all do, and it’s what we have to do. We name our destiny, our planned-for destination and our location right now, on the basis of our irrationally drawn conclusions, and what we become, ultimately, is what we expect to become. We can think, so we are not doomed like that scrawny puppy to getting the short end of every teat. But thinking takes practice, and unless we learn to think very wisely and very well, we stand at tremendous risk of dooming ourselves, simply from reasoning badly about inconclusive evidence. We can become anything we dare to let ourselves imagine. But when events fall disastrously short of our expectations too many times, what we dare to let ourselves imagine can become very, very small.

But Xavier couldn’t foresee any of that, and he was so proud of his car he seemed to glow. Surely all he had done would transcend any race results. Despite being horribly circumscribed by his mother’s proscriptions, he had mastered those manly virtues of self-reliance and application and persistence. Competition and good sportsmanship could not be beyond his moral range, and my only concern was that “Xavier’s Destiny” did not come to symbolize a month of hard work culminating in defeat.

And it was in that miasma of elation and trepidation that I entered the grade school cafeteria where the Pinewood Derby would be held.

The cars were amazing. They were sleek and low-slung and aerodynamic and utterly, utterly gorgeous. Clearly, not a single one of them except “Xavier’s Destiny” had been built by a child, but they were beautiful nevertheless. It says a little something about the minds of overcompetitive adults that they would go to such enormous lengths to teach their sons the unmanly art of cheating, but they did, in fact, go to enormous lengths.

The cheating was pandemic, to the extent that one might as well not call it cheating. Clearly, it was expected that the cars would be built by the fathers, with or without their sons’ advice, and I realized I might have done better by Xavier by talking to the dads rather than reading the rules. I don’t know what I would have done if I had talked to the dads, since I agree with the actual didactic goals of the Pinewood Derby — manly virtues, not male vices — but it left Xavier in an awful spot.

“It’s okay, Xavier,” said Mrs. Marquez. “Not everybody can be the winner.”

“No,” I said. “If you try hard and lose, you’re a winner who just didn’t win today. But if you give up, you’re a loser.”

Xavier nodded solemnly. “Balls first,” he said.

Mrs. Marquez gave me a sharp look, and I had the idea that I might have been fired on the spot as prosthetic father if I had hung around. Instead I led Xavier through the crowd to the weigh-in. The excitement was palpable. There are only thirty Cubs in Xavier’s pack, but with moms and dads and brothers and sisters and grandparents and friends, there were close to two hundred people in the cafeteria. Children were racing back and forth, shouting and shrieking, and the din was incredible. The weigh-in crew checked the width, length, clearance and weight of “Xavier’s destiny,” and it passed all the tests. The car was an eighth of an ounce shy of the five ounce weight limit, and it occurred to me that that might not be a bad thing.

We went over to the race track to prepare for our first heat. The race track is just a big ramp cut into lanes. The cars are motivated by gravity alone; they roll down the ramp and the one to get to the bottom first is the winner. Since there were so few Cubs, there were only two lanes, and the competition would consist of a series of heats, tournament style, a pyramid of competitors collapsing down to a single champion.

“Xavier’s Destiny” won its first heat convincingly. The big, boxy car got off to a slow, lumbering start, but it gathered velocity all the way down the hill and finished well ahead of the sleek low-rider it was pitted against. Xavier jumped up and down and crowed with excitement and even Mrs. Marquez looked a little more hopeful.

We drew a bye in the second round, so we got to watch as some of the most fearsomely beautiful cars, elegant machines with whimsical names like “Orange Julius” and “The Orange Avenger”, were eliminated. While I was watching the races a dad stepped up to make small talk — to be snoopy, that is.

“What do you do for a living, Mr. –uh…”

I said: “Willie.”

“So, uh, what’s your line of work, Mr. Willie?”

I hate that question. The straights don’t like it that I don’t have a straight answer for them, and I don’t like it that they don’t like it, and, truly, I’d have many more good things to say about humanity if we’d all just learn to let each other be. With a smile if not a smirk, I said, “I’m an itinerant raconteur.”

“Say what?”

“I’m an onomatopottymouth with time on my hands. Is that all right with you?”

“Hey, yeah, sure. Live and let live, that’s what I say.”

“Glad to hear it,” I said. I grabbed Xavier by the wrist and snaked to a different corner of the mob.

By the third heat, only eight cars remained. Of the twenty-two vanquished Cubs, a good ten showed up to cheer for “Xavier’s Destiny”. Surprised me, since these were the same boys Xavier went to school with, after all. But they knew that his car had something absent from all of theirs, a kid as the builder. The boys stood on either side of the track and shouted, “Ha-vee-air!, Ha-vee-air!, Ha-vee-air!,” as “Xavier’s Destiny” rolled to another victory.

The crowds grew larger in the fourth heat, more Cubs plus their brothers and sisters and even some of the parents. Little Xavier was becoming a small sensation, first because he had dared to race a car he had made all by himself, and second because that car was winning. The shouts of “Ha-vee-air!” were deafening, and the screaming when “Xavier’s Destiny” won again made my ears ring. The victory was a squeaker, which gave me pause, but the worst Xavier could do from there was second place, and that’s not such a horrible fate for a boy on his first try.

In the quiet of my mind, though, I thought that first place was out of reach. In the fifth and final heat, “Xavier’s Destiny” would face the car entered by Billy Chisholm, the pampered get of Big Bill Chisholm, a grower who had a big say in everything that happened in town. The car was named simply “Chisholm”, and I had watched it weigh in. It was low-slung and small and sleek, and you would think it couldn’t weigh more than two ounces. But, in fact, the pinewood had been carved outside and in, and the pine shell had served as its own crucible for a pool of molten lead. “Chisholm” was basically a lead slug surrounded by pine. This is all perfectly legal, of course, and the car had weighed in at a gnat’s breath under five ounces. “Chisholm” was astounding, the definitive Pinewood Derby racer. If Xavier lost, he’d lose to the best-engineered car in the race.

When the cars were lined up at the starting line, the noise was incredible. Virtually everyone was cheering for “Xavier’s Destiny”, even Billy Chisholm himself.

His daddy upbraided him. “What’s wrong with you, boy? Don’t you know it’s you against him?!”

“No, Dad. It’s you against him. You’re a grown-up. You can do anything. He’s a kid, but he’s beat every grown-up in the room. If my car wins, a grown-up wins. But if his car wins, a kid wins. Wouldn’t that be something?”

Big Bill growled, but what could he say?

Xavier shook my hand, a somber little manchild with a lot on the table. He pulled me down and whispered in my ear. “Balls first through the universe, right?”

“Right,” I whispered back. “And if you get kicked, you grit your teeth and keep on walking.”

He nodded gravely and turned to face his destiny.

Despite myself, I held my breath when the race started. “Xavier’s Destiny” got off to its usual slow, lumbering start, but it steadily gained speed, just as before. But “Chisholm” had the same weight advantage plus a low, sleek profile to the wind; it seemed as though it could slip between the molecules of air. Halfway down, “Xavier’s Destiny” was clearly behind and the room seemed to fall silent except for a throbbing hum that might have been an echo of the cheers of the on-lookers and might have been nothing more than the ringing of my own ears. My tongue was caught between my teeth and I was biting down hard, hard, hard, and I realized that nothing, nothing, nothing would make a difference now.

And just then “Chisholm” popped a wheel. It doesn’t take much impact to knock a wheel off of a Pinewood Derby racer. The axles are basically just big nails, without even a cotter pin to secure the wheels — although this is an innovation we might expect to see on the “Chisholm II”. Very probably, Big Bill had worried the wheel on and off too many times, stressing the plastic until it was as good as useless. Anyway, the car popped its right, rear wheel and went skittering sideways down the track until it shuddered to a halt. “Xavier’s Destiny” crossed the finish line and the crowd quite literally went wild.

“Ha-vee-air!, Ha-vee-air!, Ha-vee-air!” the children shouted. Someone had a tape of Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll, Part 2,” the definitive joyous noise of indoor sporting events, and some of the boys were shouting along with the call and response part: “Hey-ay! Ho-o! Hey-yay! Ho-yo!” Big Bill Chisholm was shouting that they ought to run the heat again, but since two other cars had been eliminated with popped wheels, he didn’t get anywhere. One of the boys started to bellow, “Speech! Speech! Speech!,” and soon the other boys joined in. “Speech! Speech! Speech!”

Someone thrust a microphone into Xavier’s hand, but it was much too loud for him to be heard above the shouting. “Xavier’s destiny–” he started and stopped. He smiled with pride and wonder as the noise washed over him. “Xavier’s destiny–” he tried again, but it was still too loud.

Someone bumped the gain on the amplifier and his tiny voice boomed throughout the room. “Xavier’s destiny,” he said, and the crowd fell silent.

Xavier looked to his mama. Mrs. Marquez had her hands clasped at her chest and she was smiling around a big lump in her throat. Her eyes were welled up with tears of pride and joy for her pride and joy, and I don’t think she knew just then what she had gained that day, and what she had lost forever. He looked to me and nodded, a gesture of respect for me — and for himself. He smiled to me, to his mother and to the universe.

He said, “Xavier’s destiny is the way of the eagles!”