They took one of those meandering little tarmac paths that lead down to the lake where the Swan Boats are. If I hadn’t guessed their intentions, I would have known by that alone: they were headed into a place of secluded little glens where troths are plighted left and right.By: David Ohmer

I saw the most beautiful couple walking hand in hand in the Public Garden in Boston. Physically beautiful, yes, but so much more beautiful in their souls. Doesn’t that sound stupid? And how could I possibly tell it at a glance?

You answer those questions; I tried and failed. What’s such a big deal? Holding hands in the park at sunset on a late-fall day. Could be marriage. Could be adultery. Could be a date, full of fear and torment, among secure adults beteened by circumstance. And yet… There was something different about them, and it’s my job to see that kind of thing. He might grope for a roughhewn metaphor and say they had the horizon in their eyes. And she might find a way to communicate the state of their ardor – in the nicest possible way, of course.

Anyway, I followed them. It’s what I do. Besides, I think I wanted a little taste of whatever it was they were drunk on. They took one of those meandering little tarmac paths that lead down to the lake where the Swan Boats are. If I hadn’t guessed their intentions, I would have known by that alone: they were headed into a place of secluded little glens where troths are plighted left and right. I stayed as close as I could without alarming them, and, when they chose a bench, I chose one near enough to hear even their murmuring. I had a volume of Ibsen with me, and I feigned to read from “The Master Builder” as my disguise. It seemed to fit.

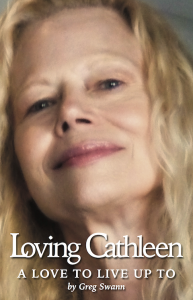

“May I confess to you?” she asked him. She was a compellingly beautiful woman. Her hair fell to her shoulders, a train of gold, and even in the half-light I could see the life burning in her blue eyes. Her features were delicate and her composure was delicate. She somehow managed to combine the dignity of a duchess with the winsomeness of a girl. She wore a dark blue frock with a bulky white cardigan, a chain of glowing gold around her neck her only ornament. Not that she needed ornamentation – or anything else. She was nothing if not perfectly proper, and yet there was something innocently feral in everything she did. Her voice was lovely, too. It might have been a contralto at full voice, but she spoke very softly in a delicate English accent. It was more than breathy, it had a kind of brushiness; it seemed to leave an enduring trail of orderly sound in the air. “I feel I must confess everything to you and then bravely face whatever punishment you might mete out.”

He could smile just in his eyes. He wasn’t a pretty man. Ruggedly handsome, but only the most discerning would give him a second glance. But, if they did, they’d see a strength in his eyes, especially when they smiled, that you don’t see everywhere. If she was the Sun crowned in gold, he was the fertile Earth, a composition in loamy greens and browns and grays. His eyes were a dusky green, but they matched hers in burning radiance. His hair was almost black, just barely brown, and on the fine edge of being shaggy, a week overdue for a cutting. He wore a charcoal business suit, nicely cut but nothing special. His face looked as though it had been cut from virgin rock. He looked like he’d make a good friend – or a superb enemy. When the smile spread to his cheeks, he said, “I think it’s me who should be confessing.”

“Oh, really? I shall enjoy punishing you, then. It’s what I’ve dreamed of, in silence and solitude. It’s been my secret shame. There. Now you know.”

The smile spread to his chest at least and he seemed to grow larger as I watched him. “Punish me how, precisely…?”

“Oh, I shall merely scold you at first. I think you could use a good tongue-lashing, don’t you? But then I’ll slap you, slap you hard. I’ll strike you again and again with the awful blows of tenderness. Really, I think there’s nothing for it but to beat you mercilessly. In the nicest possible way, of course.”

I think he might have been smiling to his toes by then, and it was fun to watch in a furtive sort of way. He said, “I guess I’d better come clean, then…”

She touched him very gently on the hand. “You can always say anything to me. Anything! You can’t be wrong. I won’t permit it.”

He chuckled. “…Okay. I think you’re fixing something in me. Fixing something I hadn’t even known was broken. Something I hadn’t even known was there… Does that make sense to you?”

She smiled in her eyes, too, but there was nothing mocking about it. “Oh, yes.”

“It’s almost as if… as if we speak two different languages, and I’d never guessed there was anything to be learned in yours.”

“There’s a lot to be learned, isn’t there?”

His lips were parted by his smile and the fire in eyes seemed to flare. “A lot.”

Her hand was still on his and now she squeezed it. “But you’ve always been a good student, haven’t you?”

“Oh, yeah. That’s what I’ve been. Always had the horizon in my eyes. Couldn’t see today for all the tomorrows in the way. ‘Works hard, shows promise’ on every report card of my life.”

Her eyebrows arched. “All but one.”

He nodded. “That’s right. All but this one.”

“Oh, no! But you do show promise. Most ardently do you show promise. Most prominently.” Her silent laughter was simply deafening.

He shrugged. “I don’t know. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks…”

“But you most assuredly can, if the old dog is willing to give it the good try. And you do seem very willing. Most enthrallingly willing, if I must reveal myself to you.”

“I want that. I want you to reveal yourself to me in every way you can imagine.”

“See there. That was almost poetical.”

“…Sometimes I think you’re laughing at me.”

She clutched his hand still more tightly. Almost silently, her breath a part of the evening breeze, she said, “Never. Always. Never.”

“Because you do bring out the poetry in me. I’d never even guessed it was there…”

She laid her head against his shoulder. “How lovely…”

“I’ve, uh… I’ve written a poem for you…”

She sat up and looked searchingly in his eyes. “You have?”

“I guess I was pretty uncomfortable doing it, but I didn’t want to stop myself.” He looked as though he were fourteen years old, an uncongealed mass of squirming yearnings. “It says what I feel, and I tried to make it funny. It’s not that special.”

She moved her hand to his forearm and squeezed it. “It’s special.”

“But you haven’t even heard it.”

“When was the last time you wrote a poem?”

“I guess… never.”

“It’s special.” She slipped her arm under his and pulled him to her. She said, “Recite it to me. Declaim your longing for me and know that I am weakened by the very thought of it.”

“…You see? That’s already better than the whole poem…”

“Stop it,” she commanded – in the nicest possible way. “Be who you are. I’m here, am I not? Do you need a greater proof of my response to you?”

The smile returned to him, fuller than before. “In fact I do…”

“Then recite the poem, vain suitor. I’m not one of your girls next door. I can’t be knocked over with a box of chocolates.”

“Okay… The title is ‘Love among the nerds.’”

“‘Love among the nerds’?”

He nodded. I think solemnly, actually.

“Fair enough. Declaim yourself.”

He did himself proud. He wasn’t Olivier, but he didn’t run from his material either.

Let’s get hitched like velcro, baby.

It’s the best thing we can do.

You stick to me like strapping tape.

I’ll stick to you like glue.

I’ll cast my anchor in your harbor, baby.

Thrust my shovel in your earth.

Cling by claws to your mountain walls.

Test me. Take my worth.

Let’s get hitched like velcro, baby.

Let’s do it till we die.

Grab me, grasp me. Clutch me, clasp me.

Hook me with your eyes.

“Well that’s quite good,” she said. “A metaphor nicely worked. Three, four – five levels in places.” He was beaming and she gently prodded his ribs with her elbow. “Not half bad. For a start.”

“I, uh… I wrote it for your voice. I love to hear you say the word ‘baby.’ I’d love it – I’d love it if you’d recite it to me sometime.”

She melted into him still more deeply, her cheek on his chest. “Would tonight be too soon?”

This is one of the stories that didn’t make the final cut for Loving Cathleen, an exploration of the most fully-committed romantic love, available now at Amazon.com.

From the murky depths of the park there came a stumbling drunk of a woman, a lumpy, dumpy pyramid of self-willed degradation dressed in filthy brown herringbone. There might have been a human being in there once, but it had been flooded out long ago by liquor and the tears of self-pity. She stopped before the lovers and said, “Urk.”

The goddess of the golden tresses looked her up and down and said, “How nice.”

The drunken woman faltered, almost fell. She said, “Oh, god.”

“But there is no god. There is only goodness.”

“Hah! I’d like to know where I could find some!”

“Goodness is within you. If it isn’t there, it isn’t anywhere.”

The drunk harrumphed, fencing off the truth with scorn. She stumbled on her way and the couple melted into each other as though nothing at all had happened.

A moment later the drunken woman threw up on her shoes. “Bwallt…!”

“Oh, look! She’s cleansing herself. How primitive.” She laughed and the nightbirds cried out in envy of the sound.

He was still looking at the drunk, perhaps in pity, and she clasped him by the cheeks and pulled his attention back to her. “You’ve been a most avid student, haven’t you? I think I should like for you to show me more – of your promise, that is.”

“Not so fast, lady. How can I punish you when I still haven’t heard your confession?”

She smiled to the core of her being. “I shall confess to you fully, sweet prince. I shall divest myself of every proud secret. I’ll conceal nothing from you, you may count on it. I will make my confession to you in the most tellingly perfect language I know. But I won’t use a word. Does that make sense to you?”

Somewhere between a croak and a whisper he said, “Always. Never. Always.”

She pulled his face to hers and kissed him more certainly than marriage, more certainly than the stately dance of the stars. After an eternity they finished, but they didn’t quite part. She spoke to him, murmured to him, her lips brushing against his. “‘Get hitched,’ eh? Is that a proposal?”

He smiled to the core of his being. “Why no. I’m sure of my answer, so I’ve been waiting for you to ask.”

“Are you so very sure of me, then?”

He answered her by kissing her back, hard, and I know that was the answer she sought. She broke from his lips to rush back to them, nibbling at him, biting at him, her tongue darting out to tease him. It was the most amazingly thrilling spectacle I’ve ever seen – and, yes, I watched.

She put her mouth next to his ear and said, “Take me right here or take me out of here, but take me, damn you!, before I am incinerated by your heat…”

He simply groaned, a perfect reply in a better language. His lips were beside her ear, brushing against her silky golden hair. He said, “Let’s get hitched like fusion, baby. Explode into the stars…”

She started to melt, I think, but then she braced herself. She stood up, then pulled him up by his hands. “If you make me any hungrier, I shall have to punish you worse.”

He smiled in his eyes, in his life. “In the nicest possible way, of course.”

“Of course…”

She walked over and stood before me, waiting patiently. I stared hard at my book even though it was full dark and I couldn’t see a word on the page. Finally I looked up and she said, “We’ll be going now.” The laughter in her eyes was raucous.

I smiled at her. I think everyone must. She rejoined him and they walked arm in arm, nestled very tightly, out of the park. To get hitched like velcro, I hope. Like fusion, I hope. Till they die, I hope.